Mountain Sickness Symptom Checker

Check for Symptoms

Symptom Analysis Results

Important Guidelines

Early signs of mountain sickness usually appear within 6-12 hours at altitudes above 2,500 meters (8,200 ft).

Warning signs: Headache, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath at rest.

Action: If symptoms worsen after an hour of rest, descend 300-500 meters immediately.

Quick Takeaways

- Mountain sickness usually starts above 2,500m (8,200ft) and shows up within 6-12hours.

- Headache, nausea, dizziness, and loss of appetite are the most common early warnings.

- Stay hydrated, ascend slowly, and take a rest day every 1,000m (3,300ft) to help your body adjust.

- If symptoms worsen after an hour of rest, descend 300-500m (1,000-1,600ft) immediately.

- Medication such as acetazolamide can speed up acclimatization, but it’s not a substitute for proper pacing.

What Is Mountain Sickness?

Mountain sickness is a collection of symptoms that occur when the body cannot get enough oxygen at high elevations. It’s also called altitude sickness and typically affects travelers who ascend rapidly without proper acclimatization.

The condition ranges from mild discomfort to life‑threatening edema. Recognizing the early signs of mountain sickness can mean the difference between a safe trek and a medical emergency.

Why It Happens: Altitude and Hypoxia

Altitude refers to the height above sea level. As you climb, atmospheric pressure drops, meaning each breath contains fewer oxygen molecules. This leads to hypoxia - a deficiency of oxygen in the body’s tissues.

Your brain is especially sensitive to low oxygen, so even a small drop can trigger the first warning signals. Understanding this physiological link helps you anticipate when symptoms might appear.

The First Warning Signals

Most hikers notice problems within the first 24hours of reaching a high camp. The following symptoms are the most reliable early indicators:

- Headache: Usually a dull, throbbing pain that worsens with movement. It’s the hallmark sign and often the first to appear.

- Nausea or loss of appetite: You may feel queasy, vomit, or simply have no desire to eat.

- Dizziness or light‑headedness: A feeling that the room is spinning or that you might faint.

- Fatigue that feels out of proportion to the effort you’ve put in.

- Shortness of breath at rest, even when you’re not exerting yourself.

If any of these show up, pause your ascent and evaluate the situation.

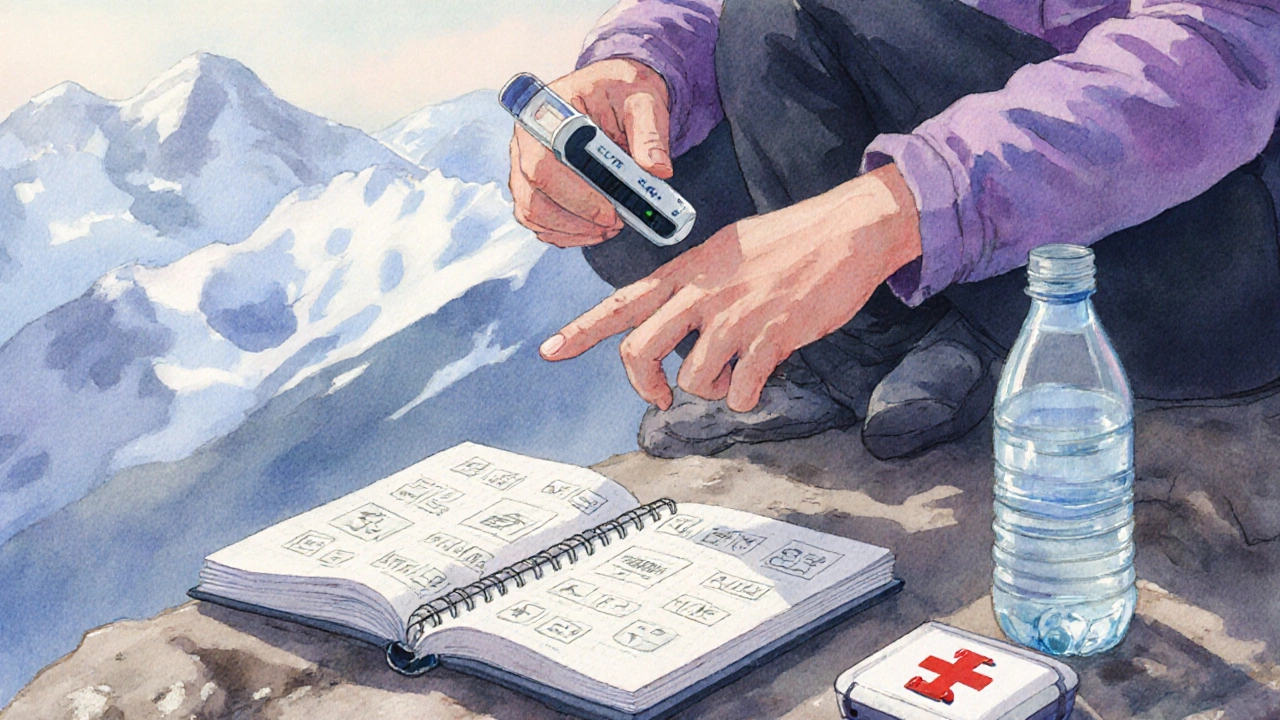

How to Monitor the Symptoms

- Keep a symptom diary. Write down the time, altitude, and severity (mild, moderate, severe) of each sign.

- Use the “Lake Louise Score” - a quick self‑assessment tool that grades headache, nausea, fatigue, dizziness, and shortness of breath on a 0‑3 scale.

- Check your pulse oximeter if you have one. A reading below 90% at rest suggests worsening hypoxia.

- Ask a climbing partner to observe your gait and speech; an outside perspective catches subtle changes you might miss.

Regular monitoring lets you make data‑driven decisions about whether to keep climbing or turn back.

When to Take Action: Descend or Seek Help

Early signs are manageable, but they can progress quickly. The table below contrasts the mild symptoms you can often treat on the trail with the severe signs that demand immediate descent.

| Aspect | Early Signs (Manageable) | Severe Signs (Require Descent) |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | Dull, improves with rest and hydration | Throbbing, unrelieved by painkillers |

| Nausea | Occasional, can keep some food down | Persistent vomiting, unable to retain fluids |

| Dizziness | Light‑headed, steady with rest | Loss of balance, inability to walk |

| Breathing | Shortness of breath after exertion | Labored breathing at rest, rapid pulse |

| Neurological | None | Confusion, inability to think clearly, ataxia |

| Fluid Retention | None | Swelling of hands, feet, or face (High‑Altitude Pulmonary/Oedema) |

If any severe sign appears, descend at least 300-500m (1,000-1,600ft) right away. Give your body an hour to recover; if symptoms persist, continue descending until they lessen.

Prevention and Acclimatization Strategies

Good preparation can stop most problems before they start. Focus on three pillars: pacing, hydration, and medication when appropriate.

- Acclimatization: Follow the “climb high, sleep low” rule. Spend a night at a lower altitude after each ascent of 500-600m (1,600-2,000ft).

- Fluid intake: Aim for 3-4L of water per day. Warm fluids also help maintain core temperature.

- Eat a balanced diet rich in carbohydrates; they require less oxygen to metabolize.

- Consider prophylactic medication such as acetazolamide (Diamox) - 125mg twice daily - if you know you ascend quickly.

- Avoid alcohol and smoking, both of which impair oxygen delivery.

These habits turn a risky climb into a safer adventure.

Common Mistakes and Myths

Even experienced trekkers fall into traps. Here are the most frequent errors:

- Myth: You can “push through” a headache if you’re determined. Reality: Headaches are a warning sign; ignoring them often leads to cerebral edema.

- Myth: Drinking coffee helps you stay awake and fine. Reality: Caffeine is a diuretic and can worsen dehydration.

- Myth: You only need to protect yourself above 4,000m. Reality: Symptoms can appear as low as 2,500m, especially in rapid ascents.

- Myth: If you feel fine at a higher camp, you’re safe. Reality: Symptoms can develop after several hours of rest.

Keep these in mind the next time you set foot on a high trail.

Frequently Asked Questions

What altitude is considered risky for mountain sickness?

Most cases start above 2,500m (8,200ft). The risk rises sharply after 3,500m (11,500ft), especially if you ascend faster than 300m (1,000ft) per day.

How long does it take for early symptoms to appear?

Symptoms can surface within 6-12hours after reaching a new altitude, but some people notice them as early as 3hours.

Can I use over‑the‑counter painkillers for the headache?

Yes, ibuprofen or acetaminophen can relieve mild headaches, but they don’t treat the underlying hypoxia. If the pain persists, descend.

Is it safe to take altitude medicines without a doctor’s prescription?

Acetazolamide is generally safe for healthy adults, but you should consult a medical professional if you have kidney disease, asthma, or are pregnant.

What should I do if my friend shows severe symptoms?

Begin an immediate descent, keep them warm, give oxygen if available, and seek professional medical help as soon as you reach a lower altitude or a base camp with facilities.

Next Steps and Troubleshooting

If you’re planning a high‑altitude trek, start by measuring your baseline fitness and getting a pulse oximeter. Test the “Lake Louise Score” at home by simulating mild hypoxia (e.g., breathing through a straw for a short time) to understand the scale.

During the climb, use the symptom diary and keep your hydration bottle within arm’s reach. If symptoms appear, follow the decision tree below:

- Record the symptom and its severity.

- Rest for 30-60minutes at the same altitude.

- If improvement occurs, continue with a slower ascent schedule.

- If no change or worsening, descend immediately.

Remember, the mountain will always be there; your health isn’t. By recognizing those early cues, you give yourself the best chance to enjoy the summit safely.

Fredric Chia

October 10, 2025 AT 00:09The guide's recommendation to descend 300‑500 m after an hour of rest is overly simplistic and fails to account for individual acclimatization variability.

Hope Reader

October 16, 2025 AT 04:00Nice rundown, but let’s be real-if you’re already choking at 2,600 m you’re not going to charm the mountain with a smile. Hydration is great, but sipping water won’t fix hypoxia. 😏

Marry coral

October 22, 2025 AT 10:00Stop glorifying pills; Diamox helps but you still need proper pacing or you’ll crash hard.

Emer Kirk

October 28, 2025 AT 12:13Wow the altitude thing is scary but also kind of beautiful I feel it in my bones and I can’t stop thinking about the summit

emma but call me ulfi

November 3, 2025 AT 15:26I get the vibe, keep it chill and listen to your body.

George Gritzalas

November 9, 2025 AT 17:16Wow, the author actually *missed* a comma after “shortness of breath at rest”. This is a tragedy of epic proportions, folks. 🙄

ruth purizaca

November 15, 2025 AT 16:20The advice feels recycled, almost as if the author read a brochure from the 1990s and never updated it.

Shelley Beneteau

November 21, 2025 AT 18:10I appreciate the thorough breakdown of early vs. severe signs. The table format makes it easy to scan, especially when you’re already feeling light‑headed. It’s also helpful that the guide stresses the “climb high, sleep low” principle, which many novices overlook. However, I would add a note about the importance of monitoring SpO₂ with a pulse oximeter as soon as the first symptoms appear. In my experience, a reading below 90 % is a clear signal to halt ascent. Overall, the piece balances practical tips with medical caution nicely.

Sonya Postnikova

November 27, 2025 AT 18:36Great guide! Your friendly tone makes the scary stuff feel manageable. Keep spreading the good vibes! 😊

Patricia Hicks

December 3, 2025 AT 19:03When you set out on a high‑altitude trek, the excitement can mask the subtle whispers of hypoxia that your body is trying to send.

The first thing to remember is that altitude does not care about your schedule; it will exact its toll the moment the partial pressure of oxygen drops below what your lungs can comfortably supply.

That is why a disciplined acclimatization plan, such as climbing no more than 500 m (1,600 ft) per day with a rest day every 1,000 m (3,300 ft), is not just a suggestion but a survival strategy.

Hydration plays a starring role-aim for at least three liters of fluid daily, and consider adding electrolytes to keep your blood volume stable.

Carbohydrate‑rich foods become your best friends up there because they require less oxygen per calorie than fats, keeping your energy levels more stable.

If you feel the classic trio of headache, nausea, and dizziness within the first six hours of reaching 2,700 m, abort the ascent and rest for at least an hour while sipping water and chewing ibuprofen if needed.

Should those symptoms persist beyond that hour, the rule is clear: descend a minimum of 300 m (1,000 ft) before the situation escalates.

A portable pulse oximeter is a cheap but priceless gadget; a reading under 90 % at rest should trigger the same descent protocol regardless of how you feel subjectively.

Medications like acetazolamide can smooth the acclimatization curve, but they are not a license to ignore the body's signals.

Always remember that caffeine is a diuretic and can accelerate dehydration, which will worsen hypoxia symptoms.

Alcohol is a no‑go at altitude; it expands in your bloodstream and further impairs oxygen delivery.

If you notice swelling in your hands, feet, or face, think high‑altitude pulmonary or cerebral edema-these are medical emergencies demanding immediate descent and professional care.

In group settings, assign a ‘symptom monitor’ to keep an eye on each member’s Lake Louise Score, because personal bias can hide serious signs.

Finally, respect the mountain: the summit will still be there tomorrow, but your health is not a guarantee.

By treating every early warning as a non‑negotiable cue to stop, you dramatically increase your odds of returning home with stories, not scars.

ariel javier

December 9, 2025 AT 19:30The guide’s oversimplifications betray a dangerous complacency that could cost lives; any self‑respecting mountaineer must demand a more nuanced protocol. Ignoring individual variability in acclimatization is a negligent shortcut.

Bryan L

December 15, 2025 AT 19:56I’ve been in that shaky‑legged state on a 3,200 m pass, and I know how terrifying it feels. Stay calm, trust your buddy, and remember you’re stronger than the altitude 😊