Stent Thrombosis Risk Calculator

Your Stent Information

Health Risk Factors

Most people who have a coronary stent think the procedure is a "set‑and‑forget" fix. The reality is more nuanced: while modern stents are safe, the idea that clots are either inevitable or impossible is wrong. This guide clears up the most common myths, explains why clots actually form, and gives you practical steps to keep your heart running smoothly.

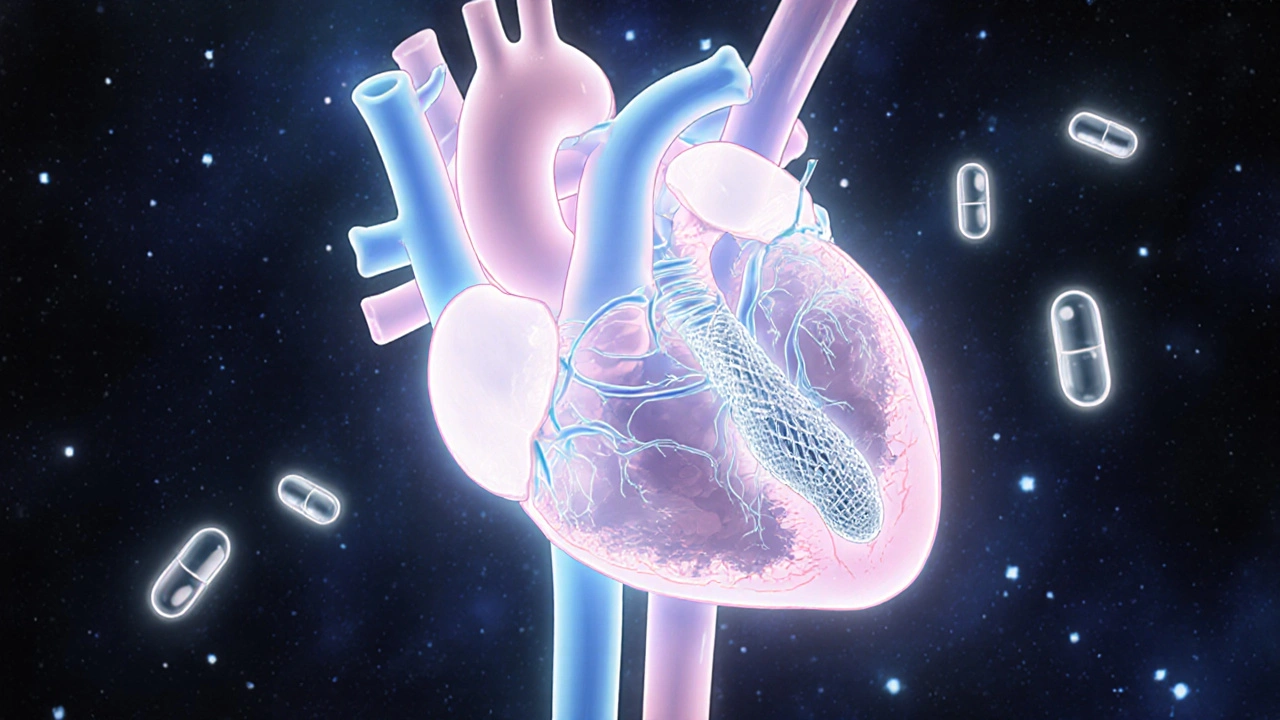

What is stent thrombosis?

Stent thrombosis is the formation of a blood clot inside a coronary stent after implantation, potentially blocking blood flow and causing a heart attack. It can happen early (within 30 days) or later (months to years). The risk depends on the type of stent, the medication regimen, and individual health factors.

Myth #1: If you have a stent, you’ll never need medication again

Many patients believe that once the metal mesh is in place, the job is done. In truth, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)-usually aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor such as clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor-is essential for at least 6-12 months after a drug‑eluting stent (DES) and at least 1 month after a bare‑metal stent (BMS). Stopping these drugs too soon dramatically raises the odds of stent thrombosis.

Myth #2: Drug‑eluting stents never clot because they release medicine

DES do release antiproliferative drugs that reduce tissue growth, but they also have a polymer coating that can trigger inflammation. Early‑generation DES (like sirolimus‑eluting stents) showed higher late‑stage clots. Newer DES with biocompatible or biodegradable polymers cut that risk, yet they are not immune. The key is proper medication adherence and routine follow‑up.

Myth #3: Bare‑metal stents are “clot‑free” and safer than DES

BMS lack the drug coating, so they cause less delayed healing, but they are more prone to restenosis-narrowing of the artery due to scar tissue. Restenosis can itself require repeat procedures, which bring clot risk back into play. Modern practice favors DES for most patients because overall outcomes (including long‑term mortality) are better.

Real risk factors that matter

- Diabetes mellitus - high blood sugar accelerates platelet activation.

- Smoking - nicotine promotes clot formation and endothelial damage.

- Chronic kidney disease - disrupts normal coagulation pathways.

- Premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy.

- Complex lesions (long lesions, bifurcations) that require multiple overlapping stents.

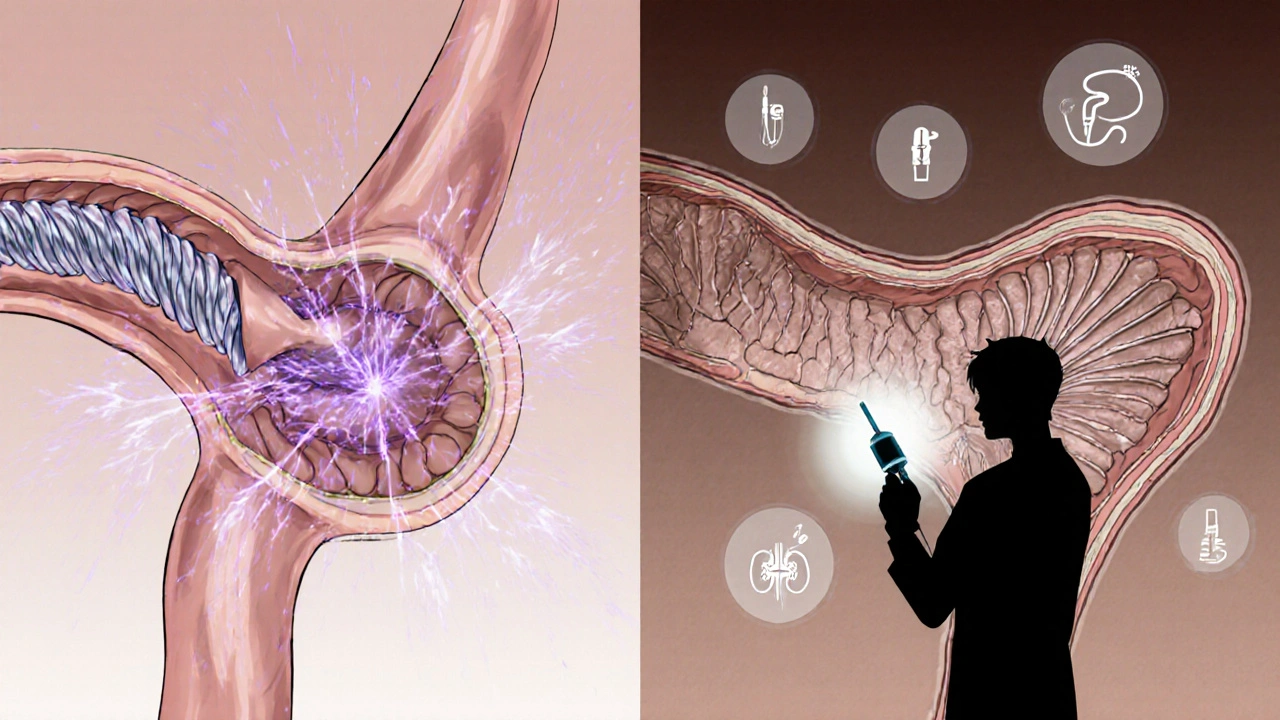

How doctors prevent and treat stent clotting

- Choose the right stent type: newer DES with biodegradable polymers for most patients.

- Prescribe DAPT for the guideline‑recommended duration.

- Use intravascular imaging (IVUS or OCT) during implantation to ensure optimal stent expansion.

- Schedule regular follow‑up stress tests or coronary CT angiography if symptoms recur.

- If clot occurs, immediate percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with thrombectomy and possibly a repeat stent is performed, alongside aggressive antithrombotic therapy.

Drug‑eluting vs. Bare‑metal stents: what the numbers say

| Feature | Drug‑eluting stent (DES) | Bare‑metal stent (BMS) |

|---|---|---|

| Late stent thrombosis (≥1 year) | 0.5-1.0 % | 0.3-0.5 % |

| Early stent thrombosis (<30 days) | 0.3-0.5 % | 0.2-0.4 % |

| Restenosis (need for repeat PCI) | 5-8 % | 20-30 % |

| DAPT duration (guideline) | 6-12 months (often longer for complex cases) | 1-3 months |

| Typical cost (US$) | $2,500-$3,200 | $1,500-$2,000 |

Patient checklist: keep your stent clot‑free

- Take all prescribed antiplatelet meds exactly as directed.

- Never skip a dose, even if you feel fine.

- Report any new chest pain, shortness of breath, or unusual fatigue immediately.

- Maintain a heart‑healthy lifestyle: quit smoking, control diabetes, and exercise regularly.

- Schedule and attend all follow‑up appointments; ask your cardiologist about any needed imaging.

Frequently Asked Questions

How early can stent thrombosis occur?

It can happen within the first 24 hours, but most cases occur in the first 30 days after implantation. Early events are usually linked to procedural issues or premature medication stoppage.

Can a stent clot dissolve on its own?

Rarely. Small clots might resolve with aggressive antiplatelet therapy, but most clinically significant clots need an urgent PCI to restore blood flow.

Is aspirin enough after a stent?

No. Aspirin alone does not provide the platelet inhibition needed to prevent stent thrombosis. A P2Y12 inhibitor is required as part of DAPT.

Do newer DES eliminate the need for long‑term medication?

Newer DES reduce late‑stage clot risk, but guidelines still recommend at least 6 months of DAPT for most patients. Stopping early can nullify the benefit.

What lifestyle changes matter most?

Quit smoking, keep blood pressure and cholesterol in target ranges, manage diabetes, stay active (150 minutes of moderate cardio weekly), and maintain a balanced diet low in saturated fats.

Understanding the facts behind stent clotting helps you and your doctor make informed choices. By debunking myths, following evidence‑based medication plans, and adopting a heart‑healthy lifestyle, you dramatically lower the odds of a dangerous clot.

Jay Kay

October 19, 2025 AT 16:12Okay, let me set the record straight. The idea that a stent is a magic bullet is pure fantasy. You still need meds and follow‑up, otherwise you’re courting disaster. The myths in this article are exactly the kind of nonsense that gets people complacent. Think twice before you start bragging about a "set‑and‑forget" heart.

Jameson The Owl

October 30, 2025 AT 15:12The notion that stent technology is somehow insulated from the machinations of larger health agendas is a comforting but ultimately false narrative. Historically the pharmaceutical industry has lobbied heavily for prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy because it serves their profit models. Moreover the data on late‑stage thrombosis in early‑generation drug‑eluting stents were downplayed in mainstream journals to protect market confidence. The regulatory bodies, beholden to political pressures, often issue guidelines that favor brand‑name devices over cheaper alternatives. Patients are thus steered into a cycle of dependency on expensive medication regimens that keep the industry afloat. Even the claim that bare‑metal stents are clot‑free ignores the reality that restenosis can lead to repeat interventions and subsequent clot risk. The article’s emphasis on “biodegradable polymers” is a marketing spin that distracts from the fundamental truth that any foreign object in a vessel poses a clotting challenge. In short, the real risk factors are not just biology but the structural incentives built into the system.

Rakhi Kasana

November 10, 2025 AT 15:12There’s a lot of drama in the way these myths are presented, but the facts are pretty clear. Dual antiplatelet therapy isn’t optional – it’s a cornerstone of post‑stent care. Even the newest DES can provoke inflammation if the polymer isn’t handled correctly. Bare‑metal stents still have their place, especially when patient compliance is an issue. The key takeaway is that you can’t ignore the medication schedule.

Sunil Yathakula

November 21, 2025 AT 15:12hey guys, totally get the concern – i’ve been there. just remember that staying on the meds is the real hero move. don’t let the scary words stop you, keep the doc appointments and keep the aspirin flowing. u’ll do fine!

Catherine Viola

December 2, 2025 AT 15:12From a rigorously analytical perspective, the recommendation to maintain dual antiplatelet therapy aligns with the consensus of major cardiology societies. The procedural intricacies described herein are corroborated by peer‑reviewed evidence, and any deviation from the protocol should be justified by documented contraindications. It is incumbent upon practitioners to convey the necessity of adherence to patients in unequivocal terms.

sravya rudraraju

December 13, 2025 AT 15:12Let us delve into the broader context of stent selection and post‑procedural management. Contemporary guidelines underscore the superiority of drug‑eluting stents with biocompatible polymers in reducing restenosis rates, yet they also acknowledge a small residual risk of late thrombosis. Accordingly, the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy must be individualized, accounting for patient‑specific risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and smoking status. Moreover, intravascular imaging modalities, namely IVUS and OCT, have become indispensable tools in optimizing stent deployment, thereby mitigating malapposition-a known catalyst for thrombus formation. Regular surveillance, via stress testing or coronary CT angiography, remains essential for early detection of ischemic symptoms indicative of stent compromise. In the event of acute thrombosis, emergent percutaneous coronary intervention, complemented by thrombectomy and intensified antithrombotic regimens, constitutes the standard of care. The convergence of precise device selection, meticulous procedural technique, and stringent pharmacologic adherence represents the triad that ultimately safeguards long‑term patency.

Ben Bathgate

December 24, 2025 AT 15:12Look, the article is fine but it’s missing the point that many patients just ignore the med schedule. They think “I feel fine, why keep taking pills?” That’s the real danger. Stick to the plan or you’re asking for trouble.

Ankitpgujjar Poswal

January 4, 2026 AT 15:12Exactly, adherence is non‑negotiable. If you’re cutting corners, you’re courting a clot. Stay disciplined, follow the regimen, and keep your follow‑ups on schedule.

Christopher Burczyk

January 15, 2026 AT 15:12The data presented in this guide are consistent with the latest consensus documents from the ACC/AHA. It is imperative to recognize that stent thrombosis, while infrequent, carries significant morbidity. Accordingly, the recommended duration of dual antiplatelet therapy remains a cornerstone of preventive strategy. Clinical decision‑making should integrate individual risk profiles, including comorbidities such as diabetes and renal insufficiency. Ultimately, a personalized approach, grounded in evidence‑based guidelines, optimizes patient outcomes.

Caroline Keller

January 26, 2026 AT 15:12It’s heartbreaking to see so many people treat their heart like a disposable gadget. The moral imperative is clear: you owe it to yourself and your loved ones to honor the medical advice. Ignoring medication is not just selfish-it’s reckless. Let’s champion responsibility over convenience. The stakes are too high for half‑hearted effort.

dennis turcios

February 6, 2026 AT 15:12The article hits most of the key points but could be tighter on the statistical nuances. For example, the exact incidence of late thrombosis varies by stent generation and patient demographics. Also, the role of platelet function testing in guiding DAPT duration deserves a mention. Overall, solid groundwork, just needs those extra data layers.

Felix Chan

February 17, 2026 AT 15:12Great info, keep it up!